The French have never quite forgiven Maltese “indiscretion” even though over 220 years have passed but the name of Malta still smarts with some French historians and some politicians. Nor have they forgotten!

Politically, Malta and France are equal members in the EU and generally both respect equally and respect each other geopolitically, but somehow there is not that “chummy friendliness” which Malta enjoys with Great Britain and Italy – and indeed, Libya.

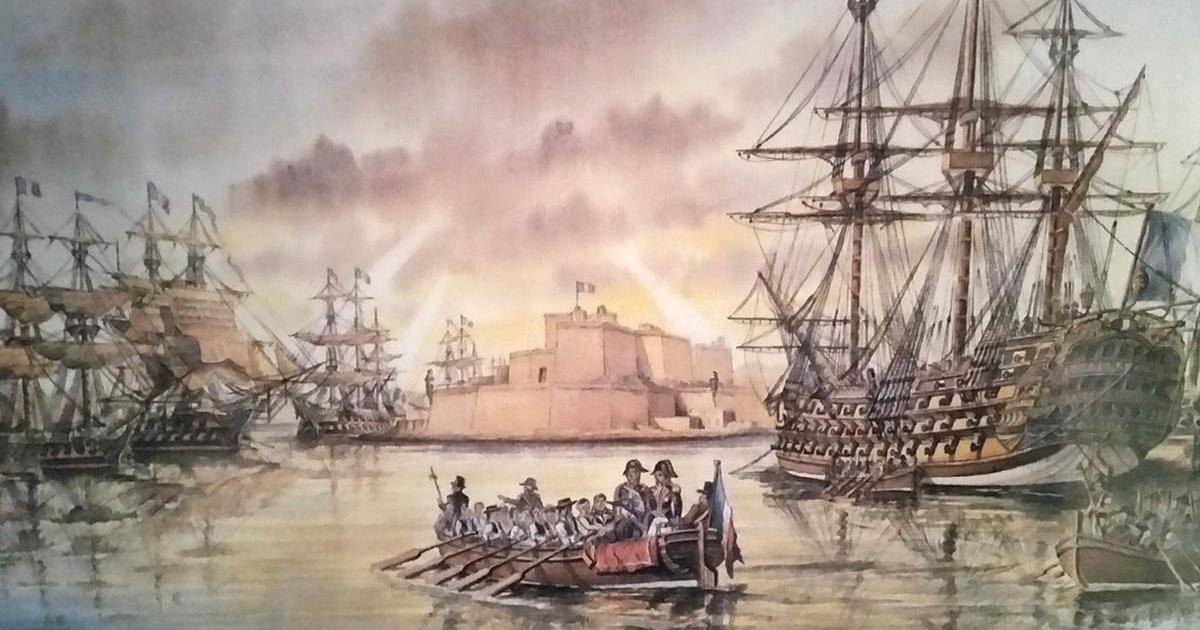

In 1798, a massive French fleet with 30,000 soldiers on board under the command of General Napoleon Bonaparte left Toulon and anchored off Malta on the way to an “expeditionary” tour of Egypt. Malta was then still under the Knights of the Order of St John of Jerusalem but by then the Order had been weakened and had lost a lot of its influence.

Napoleon Bonaparte quickly sensed that Malta was an important possession as the key to power in the Mediterranean and the route to Asia via Egypt and the Red Sea, particularly with the British Mediterranean Fleet under Admiral Horatio Nelson anchored in nearby Sicily.

Under the pretence of needing replenishment of supplies, French warships entered the Valletta Grand Harbour demanding water. At first Grand Master Hompesch flatly refused but almost immediately capitulated in view of the massive French numbers.

The French Occupation of Malta had begun.

Still very much fired by the spirit of the French Revolution, Napoleon took Malta by storm and during the six days he spent on the island set about trying to eradicate every trace of the “bourgeois” royalty of the Knights. In a whirlwind of activity – amongst others – he overhauled the educational and judiciary systems (Malta still carries traces of the overhaul to today) and set about dismantling the influence of the Knights and the Roman Catholic Church.

The French soldiers ran amok, looting churches and stately buildings. This triggered the chagrin of the Maltese population and in one ruse the silver-encrusted railings of St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta were painted black to escape detection – which they did.

During the two years of occupation, Maltese rebellion reached fever pitch. Secret dispatches passed between the Maltese leaders (including leading members of the clergy) and Admiral Nelson and finally culminated with an “invitation” to the British Fleet to invade Malta. Nelson duly obliged and in 1800 the Maltese tore down French flags from buildings and flew the Union Jack.

Malta became a British possession and part of the British Empire and remained that way until Independence in 1964.

This rebellious affront to French revolutionary rule and even more ghastly a downright rejection of Napoleon Bonaparte who was after all a fellow Mediterranean islander having been born in nearby Corsica, certainly did not go down with the French.

The sentiment that the Maltese had helped overthrow the French and had substituted them by the old arch-enemy “perfidious Albion” was even more galling and humiliating.

Decades have rolled by but the needle still remains. Some years back the French Government (before Malta’s EU entry) took the unprecedented step of banning all Maltese wine exports to France – as if this was in any way going to provide a threat to French wines!

Former French President Nicolas Sarkozy pronounced that Malta “should not enjoy the same Parliamentary rights” as other EU members because of its small size.

However, the major dispute remains the special sword manufactured for Grandmaster Jean Parisot de la Valette in Malta.

La Valette is a Maltese hero. As Commanding Officer he heroically repelled the Ottoman Siege and Invasion in 1565 and then was instrumental to the building of Malta’s capital city as a bastioned enclave and appropriately named Valletta for him.

The sword is of immense value as the hilt is jewel-encrusted and is nowadays worth well over €500,000. Naturally, it has enormous significance in Maltese history. When Napoleon’s troops ransacked the island, the sword disappeared and years later appeared in the Paris Louvre Museum where it remains today.

Repeated Maltese requests of “may we have OUR sword back please” have fallen on deaf French ears. The French maintain that as Parisot de la Valette was French, the sword belongs to France. Malta claims the sword is of great symbolic and historical value to the islands and must therefore be returned (shades of the Elgin Marbles and a vast booty of Ancient Egypt relics looted by both France and Britain!).

Some of the changes made by Bonaparte in his short stay have remained, that is legally and in the educational system as well as medical and some years back the sword was “lent” to Malta for a few days for an exhibition, but the French ensured it was returned tout-de-suite!

There the impasse remains and no amount of EU “fraternity” has moved the French to re-think otherwise.

ALBERT FENECH