By Albert Fenech

The island of Malta is riddled with underground tunnels and the two islands of Malta and Gozo abound with caves, caverns and hiding holes. Humans have wild imaginations and as far as tunnels, caves, caverns and holes are concerned, the imagination of human beings down through the years has run amok with wild explanations and interpretations.

This has spawned a myriad of theories and speculations that Malta was the nerve-centre of the lost continent Atlantis (some tunnels are even submerged under the Mediterranean), that sub-humanoids were once seen emerging from an underground tunnel, that secret cities thrived underground and all sorts of wild explanations.

These are mainly concentrated around the Hypogeum at Tarxien and a number of multi-religious catacombs in the northern Rabat area. The simple explanation is that these are extensive underground burial chambers, the Hypogeum stretching back to the Stone Age and Bronze Age eras and the Rabat catacombs pioneered by the Romans who strictly forbad burials within city walls.

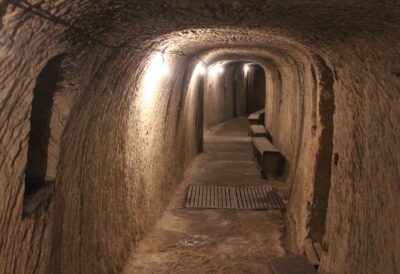

Enormous speculation was further fuelled some 15 years ago when an extensive network of underground tunnels were excavated under Malta’s capital city Valletta, built in the latter part of the 16th Century and officially inaugurated in 1568 – relatively new for a European capital city and in fact one of the latest in the European continent.

As usual, the human imagination began to out-leap itself with interpretations of a ‘secret city’ constructed by the Knights of Malta when they had Valletta built as a further fortification against the rampant Ottoman Empire; that these tunnels were built and stretched under most of Malta and provided escape passages leading to sea in case the city came under siege and that these were tunnels of what were termed as ‘The Lost Crusaders’. Speculation became even rifer with explanations of secret carriageways and underground military labyrinths.

These explanations spread so fast that they were actually featured in a March 2009 edition of ‘National Geographic’ magazine.

‘Geographic’ reported the tunnels were discovered on 24th February, 2009 while excavations were being considered for a large underground car park under the magnificent Knights’ Palace in Valletta.

Survey Leader of the Valletta Rehabilitation Project Claude Borg was quoted as saying, “A lot of people say there are passages and a whole new city underground, but where are these underground tunnels, and do they exist?”

Well, they certainly do exist and I have known about them since I was a young boy, as has the most of Malta and indeed the world. During World War II, one of the tunnels at Lascaris, in the south of Valletta, was used as British Services underground headquarters as War Rooms. Other tunnels were used as air raid shelters.

The more recent discovery uncovered an even larger network of tunnels and there are valid and logical reasons why they were originally constructed when Valletta was built. It seems the tunnels were constructed as an ahead-of-its-time water and drainage system.

Definitely they date back to the 16th and 17th Centuries. Although they are high-ceiling enough to enable a comfortable passage for human beings, the tunnels are estimated to have secured a vital system of piped water to Valletta and its inhabitants, still conscious of the bloody siege of Malta by the Ottoman Turks in 1565.

The first aspect to be excavated in early 2009 was a vast underground cistern and reservoir under the Palace Square. It is some 40 feet deep with a large hole in one of the reservoir walls, acting as a piping system to provide water for the Grandmaster’s Palace and other areas of Valletta.

Malta Heritage Trust restoration architect at the time, Edward Said said there is evidence to show that the tunnels were an efficient plumbing system, complete with ancient passages for access and maintenance.

Securing water supplies was a major priority and water was transported to Valletta from valleys to the west via an aqueduct that runs all the way from Rabat in the north and parts of which are still standing.

Lead pipes and metal valves have also been found that regulated a large fountain in Valletta’s Palace Square, a fountain that was dismantled by the British but which has now been restored.

One other important aspect was awareness that plague could strike at any time, propagated by lack of hygiene and hence the new city needed an efficient drainage system.

This induced architect Said to remark that while Valletta enjoyed a relatively hygienic drainage system in the 16th and 17th Century “by comparison major cities like London and Vienna were still wallowing in their own muck”.

ALBERT FENECH

salina46af@gmail.com