By Albert Fenech

It cannot be denied that Malta has a past of colonial enforcement, stretching back to Roman times, the 500-year dominance of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, the brief span of French colonialism and finally the 150 year dominance by the British Government.

Despite the occasional protests of the Maltese, the majority of years were rules of what the colonial masters required – with the Maltese having an almost non-existent outlet for their circumstances and their day-to-day life. Their existence was “we order, and you obey”.

Thus, the happenings on 7th June 2019 have a primary place in Malta’s modern history in a process of which the islands had never experienced previously.

Malta and Gozo had just undergone the rigors of World War 1 when it became known as “The Nurse of the Mediterranean” because of the geo-social position in the centre of the Mediterranean Sea, where thousands of military and civilian personnel were medically tended.

Malta and Gozo were not on the battle front but their activities had a very telling part in the final outcome and the victory of the Allied forces (just as in World War II).

The local inhabitants had suffered much hunger and deprivation as the best was used for the recovering wounded, local employment was minimal and little thought was given as to coping and in addition, very much paramount, was the substantial cache of those who politically activated that Malta’s future lay with Italy and not “the foreign British”.

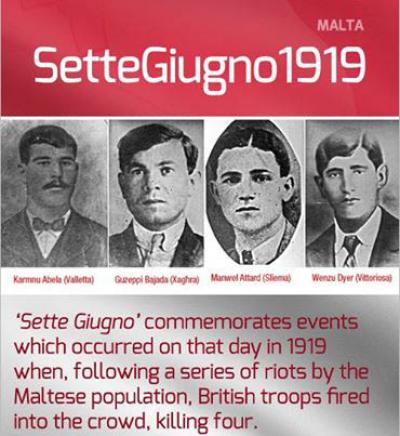

Angers flared and came to a head in what became known as the Sette Giugno (Italian: “Seventh of June”) which became a Maltese national holiday to be celebrated annually on 7th June as this uprising being part of international importance.

This led to riots on 7th July, 1919, over the rising cost-of-living and British troops eventually managed to suppress the riots, killing four in the process. The riots and the British colonial government’s response to them led to increased anti-colonial sentiments among the Maltese public, while Fascist Italy and ethnic Italians in the colony viewed the riots as an opportunity to promote Italian irredentism in Malta.

Thus, Sette Giugno brought to light a spike of different factions with difference interests, the local inhabitants feeling discomfort and hungriness, the pro-Italians clamoring for unity with Italy and the pro-British sensing the importance of Malta in the Central Mediterranean region, an importance which became crucial during the Second World War between 1939 and 1945.

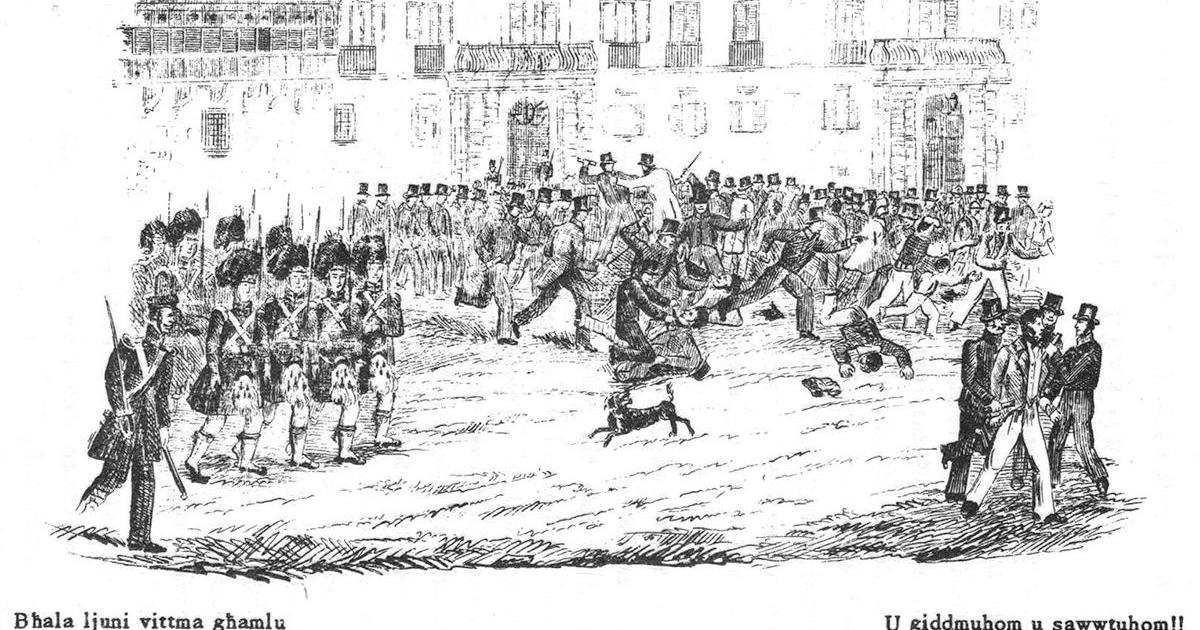

The first spark of unrest centred on the Maltese flag defaced with the Union Jack flying above the shop outlet “A la Ville de Londres.” Unlike the previous meeting, the shop was now closed. This did not prevent the crowd from forcing itself inside, to remove the flag and flagpole.

This incident sparked the uprising. The death of the President of the Court some days earlier had required all governmental departments to fly the Union Flag at half mast, including the Bibliothèque buildings in Pjazza Regina, and the meteorological office. The crowd proceeded to the Officers’ Club, insisting that the club’s door had to be closed. Window panes were broken, while officers inside were insulted. Police officers trying to restrain the mob were also assaulted. The crowd then returned to the front of the Bibliothèque, shouting for the Union Flag to be taken away; it was promptly removed by the men on duty.

The crowd moved on to the meteorological offices, housed in a Royal Air Force turret. After breaking the glass panes, the mob entered the offices ransacking and destroying everything inside. Some individuals climbed onto the turret, removing the Union Jack and throwing it into the street. The crowd burned the flag along with furniture taken from the offices nearby.

The mob then moved back to Palace Square, where they began to insult the soldiers detached in front of the Main Guard buildings. The N.C.O. that was responsible for the watch had the doors of the building closed, as were the doors of the Magisterial Palace across the square.

In Strada Teatro (Old Theatre Street), the offices of the Daily Malta Chronicle were broken into, with pieces of metal jammed in the workings of the presses to break them. While this was taking place, other crowds were attacking the homes of perceived supporters of the Imperial government and profiteering merchants in Strada Forni (Bakery Street).

It has to be noticed that leading street names at the time – particularly in Valletta – had Italian names

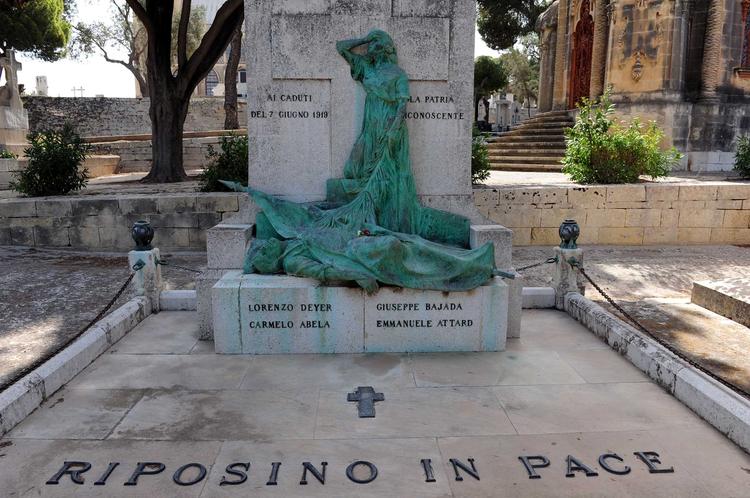

The four Maltese who lost their lives on Sette Giugno 7th June, 2019 were Carmelo Abela, Manuel Attard, Guze’ Bajada and Wenzu Dyer (who was obviously of British descent!) and will be remembered there-ever after as the first Maltese martyrs for the total independence of Malta and Gozo.

As a result of the riots, the newly-fledged Malta Labour Party gained in support and presence as the “true” representatives of Malta and Gozo and the people.

The Italian faction remained strong to and formed the Malta Nationalist Party with a strong direction that Malta should be a part of Italy under an Italian Government with the British being totally evicted.

This continued to spread onto World War II and severe internal conflagrations as an extensive corp honoured Mussolini and his Fascist Government.

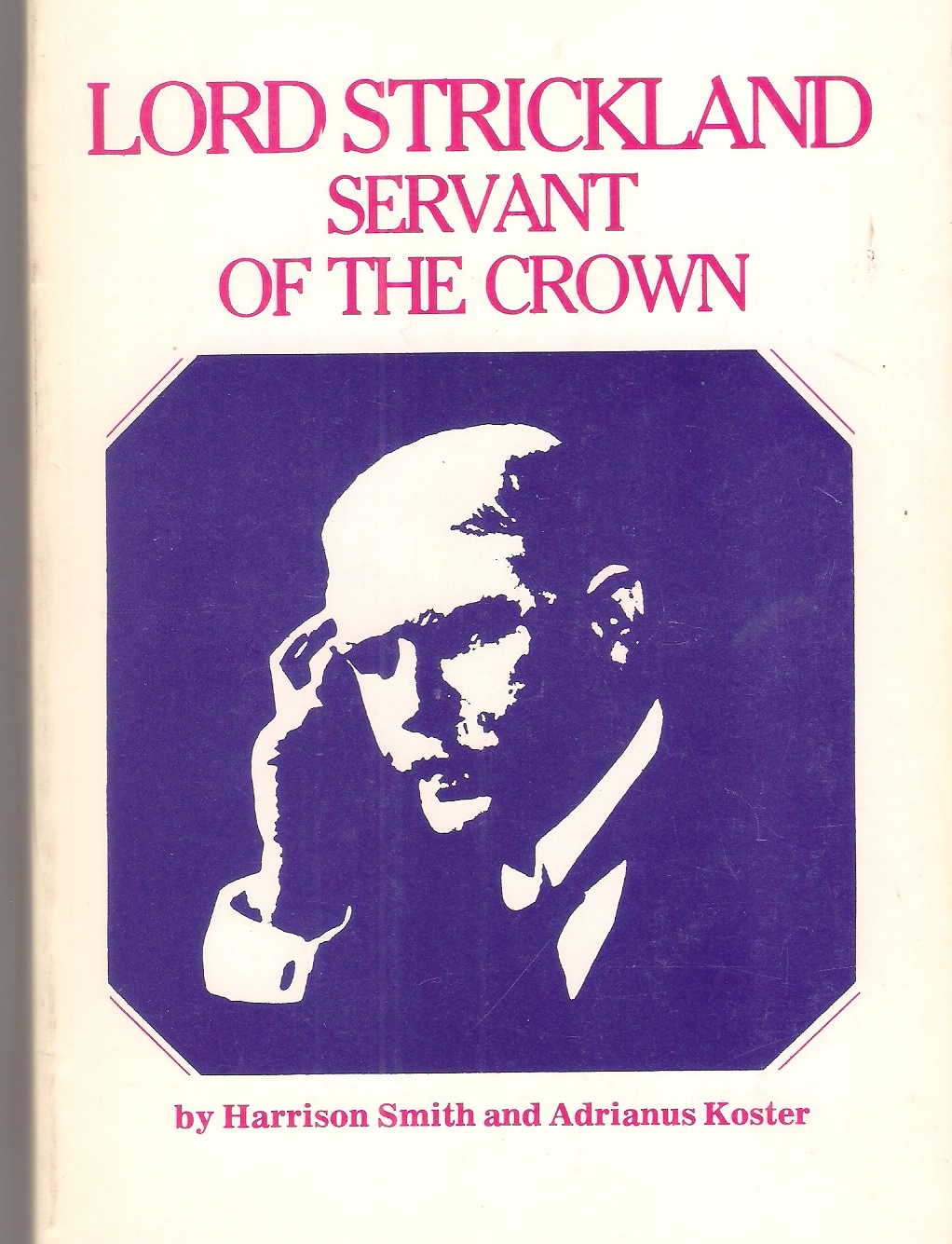

The Progressive Party, under the leadership of the Anglo-Maltese Lord Strickland and his family was obviously much-favoured by the administrators as Malta’s “true Government”, and all these elements were the internal background of Malta and Gozo – as if they were a back-cloth to the array of harsh aerial bombing and marine efforts by the Italian navy to land on Maltese shores.

All of these were the confused background which was originated by Sette Gungio to highlight all the internal movements under the heavy destruction of Nazi bombing.

From 1945 onward, many of these were trust aside and a new scenario leading to the actual independence of the two islands began.

ALBERT FENECH